The Soviet sleeper cell with a portable nuke has been replaced by the radical Muslim sleeper cell with a portable nuke.

Good morning, citizens. Today marks the 65th anniversary of the Trinity Test, the first test of an atomic bomb. While the bomb’s true capacity, the numbers of people it would wipe clean from this earth, and its embodiment of the sordidness of mankind would become known over the skies of Japan mere weeks after its trial in the wicked southwest desert of the United States, the test alone would serve to uproot traditional notions of life in the free world.

Videos by VICE

Bill Geerhart of CONELRAD.com is a cold war pop culture expert. Motherboard spoke with him via email on the eve of this historic day. We riffed on atomic culture and considered comparisons between yesteryear and today. Before we’re completely obliterated, read our conversation below, and see Bill’s special Trinity Day post.

What else was happening the day of the Trinity Test?

President Truman was in Germany for the Potsdam Conference – the last wartime summit meeting of the “Big Three” allied leaders. Churchill had already arrived, but Stalin was delayed, so Truman took the opportunity to tour a devastated Berlin in an open car. In terms of world news, this was the major event of the day. A headline from the Oakland Tribune is characteristic of the other big news of July 16th: “Four Jap Cities Fire Bombed.” But if you browse inside the paper, you’ll see that life was pretty normal otherwise – the society pages had news of engagements and weddings; there were movie listings, comic strips, baseball results, etc. It was just a routine day.

What notions of reality were shattered that morning?

The overwhelming success of the Trinity Test re-wrote the calculus that a land invasion of Japan would be necessary to end the war in the Pacific if the Japanese refused to surrender. But the biggest notion of all – that man could not destroy the world by his own hand vanished in the New Mexico desert on the morning of July 16th.

What is your sense of the public’s interest in atomic weapons and how have Weapons of Mass Destruction sculpted generations? You consider these notions in your dissection of Mutated Television and how “disorienting” it must have been. What kinds of repercussions come when the public’s interest is filtered through a distorted lens?

I think that the Bomb is viewed by a majority of the World War II generation as a savior. There is a woman featured in Ken Burns’ documentary “The War” who says as much. This attitude changed radically when the Soviets detonated their first atomic weapon in 1949 – much earlier than predicted. Cold War civil defense activities begin to escalate at this point and by the mid-1950s the government was conducting nationwide “Operation Alert” drills. The public could not help but be interested in Weapons of Mass Destruction because it was a reality that was staring them in the face from their newspaper every day. As we now know from some of the things that President Eisenhower said and wrote privately at the time, he was highly dubious about how effective government could be after World War II. The purpose of these civil defense displays was to sell the notion of survival, help calm the public and allow government to pursue an arms race.

But if you talk to baby boomers today, anecdotally at least, it is pretty obvious that these measures had the opposite effect of “calming” them. On CONELRAD.com we have the stories of people who—as children—were more or less forced to wear dog tags and get blood type tattoos for civil defense identification and triage purposes. In the case of the tattooed kids – they were literally scarred for life because of the Cold War. And then there was the atomic fear that crept into all forms of the popular culture – from music to books to movies to television. The mixed messages sent by government and the mass media about the Bomb and the Cold War helps explain how discombobulated society became in the Sixties and Seventies.

What would you say the Bomb’s lasting effects are on us?

Unfortunately, I think the power of the Bomb is wearing off as the early Cold War generation grows older. That generation will never forget the heightened fear that they lived through – particularly during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. The main reason the 1983 TV movie The Day After (clip) was such a big deal was that it was the first time that a mass audience was exposed to what nuclear weapons could potentially do to the United States. There had been cinematic depictions before, but none on the scale of The Day After. The awareness and viewership of the movie was so high that the Reagan administration dispatched Secretary of State George Schultz to appear on a live news special that followed the broadcast. His mission was to lessen the impact of the movie and he did not look happy to be in that position.

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, nuclear war has receded from the popular culture – replaced with action-friendly, single use depictions of nuclear weapons. Shows like 24 and movies like The Sum of All Fears have helped to diminish the power of the Bomb by using it as a cheap money shot that has few real consequences – Jack Bauer and Jack Ryan dust themselves off and live to fight another day. Young people growing up today playing post-apocalyptic video games have little appreciation of what a real nuclear exchange would be like. The depiction in The Day After is far from perfect, but it was a serious examination of the use of nuclear weapons.

Who were the key players in shaping the way the news of the atomic bomb was disseminated after the bombing of Hiroshima?

The military administrator of the Manhattan Project, Major General Leslie R. Groves, was the person most responsible for how the first news of the Bomb was released to the public. [Major] Groves was involved in the shaping of the first statements that President Truman made on Hiroshima as well as the subsequent press releases that went out about how the Bomb was produced. Groves recognized early on that there would be an insatiable appetite for news about the Bomb after its first military use, so he recruited a prominent New York Times science writer named William Laurence to witness and write embargoed stories about the progress of the Manhattan Project. It was Laurence, in his capacity as a consultant to the military, who wrote most of the press releases that were released by Groves to the media. These press releases would be published unedited in many newspapers because they had no original reporting to augment the official message.

It wasn’t until John Hersey’s landmark reporting on Hiroshima was published in the New Yorker magazine that the public got its first unvarnished view of what happened there—a full year after the bombing. The fascinating story of how the news of the Bomb was managed is explored at length in the book Hiroshima in America: Fifty Years of Denial by Robert Jay Lifton and Greg Mitchell.

How does war interrupt popular culture in the United States?

If it is a war that impacts everyone—like the World Wars, Vietnam and the Cold War—the popular culture begins to reflect the experience rather quickly. Vietnam and the Cold War were different from the World Wars in that the mass media did not shy away from exploring the negative aspects of these conflicts.

There was a lot of pro and con sentiment with regard to these wars and the media reflected these attitudes. There are thousands of examples of books, songs, movies, plays, etc. that capture the experience of these wars because they touched so many lives. But because the United States now has a voluntary military, the current wars in Iraq and Afghanistan do not have the same impact on the culture that previous conflicts had. The effects of the current wars are felt by a much smaller pool of people. This helps explain why the movies that have been made about Iraq—even The Hurt Locker —have done poorly at the box office.

How did popular culture, both as a force to propagandize the heroism of the United States and as a force to revolt against that notion, start to pave the way to subcultures and an awakening to new ways of interpreting reality?

I think as we matured and became more educated as a culture, propaganda became less effective as a tool of control by the government. Of course, the Vietnam War and Watergate ushered in an era of cynicism that government has yet to recover from. The failure of the mainstream press during the run-up to the Iraq War has added a new layer of cynicism. We live in a society where media is fractured and people are turning more and more towards the news source that reinforces their own view of reality. In my opinion this will eventually lead to a less informed public and a more dangerous world.

What is the “fallout” of an event or period on popular culture and how does it help society survive and rebuild?

Pop cultural “Fallout” is the evidence in art of how an event or period has impacted our collective psyche. The obvious example is the genre of B sci-fi films in the 1950s that featured mutated monsters caused by atomic testing. There were a few movies from this period that tackled the Bomb and radiation head-on like Arch Obler’s Five, but the majority relied on aliens or monsters to provide a comfortable allegorical distance for the audience. It sounds absurd, but I think both of these approaches helped Americans process the enormity of the Bomb at a time when the government wasn’t being forthcoming about the actual effects of an all-out nuclear war. I think this processing helped people, on some level, move on – even if they laughed about it as kitsch years later.

How and why did you become so interested in Cold War culture?

I grew up in the seventies in a suburb of Washington, D.C. and I remember hearing—even at that late stage in the Cold War—air raid sirens being tested every month. The fact that Washington was target number 1 and we would all be incinerated immediately in the event of a war made the siren testing especially ridiculous. As a teenager I remember Physicians for Social Responsibility coming to my very enlightened high school and showing a film juxtaposing footage from Hiroshima and civil defense propaganda. It was a very effective educational tool because it used shock and humor and I’ve never forgotten the experience. Of course, The Atomic Café documentary used a similar approach, but improved upon it by forgoing the use of a narrator and adding Cold War music as a soundtrack. But overall, I think there is something irresistible about trying to conceive of the unthinkable and that is what really draws me into the pop culture of the Cold War.

There are so many great movies, TV shows and books that have tried to imagine the end of the world. It is endlessly fascinating to consider these fictional works and then examine the real government contingency plans.

Do you remember your first encounter with the popular culture of the Atomic Age?

Probably the mutants praying to a Bomb in the ruins of the New York City subway system in Beneath the Planet of the Apes. That just amazed me.

From Beneath the Planet of the Apes, 1970.

How does the original civil defense planning of the 1950s dovetail with our more recent obsessions with readiness and terrorism?

In many ways, the reaction to 9/11 is a re-run of the reaction to the early Cold War. George W. Bush’s establishment of the Department of Homeland Security is torn directly from the playbook of Harry S. Truman. In fact, a lot of the infrastructure created during the Cold War by Truman and Eisenhower is still being used today. It was Truman who created the first federal civil defense agency. Truman also created by executive order the CONELRAD emergency broadcasting system which has evolved into the Emergency Alert System. The government relocation sites that were built at enormous cost in the 1950s (such as Mount Weather and Site R) are still being used in the current War on Terror. If the Washington Post hadn’t exposed the congressional relocation site under the Greenbrier resort in West Virginia, you can bet it would still be in operation, too.

There is a definite continuum of “Continuity of Government” strategies developed during the Cold War that are still in existence today – the bunker-directed aftermath of the 9/11 attacks had its roots in Cold War planning. There is also a continuum of the fear and paranoia that was a hallmark of the Cold War. The Soviet sleeper cell with a portable nuke has been replaced by the radical Muslim sleeper cell with a portable nuke.

To think that at any moment, your city could just disappear. Despite the funneling of fear into our society, what keeps us from going insane every day? What do you think about your city simply evaporating? Are you prepared?

I think Americans are expert at subconsciously displacing their fears and focusing on mundane things. It is a lot easier to obsess about the latest celebrity meltdown or iPhone than it is to ponder how easy it would be for a terrorist organization to nuke the port of any major coastal city. As for myself, I am ashamed to admit it, but I will probably wind up being one of those mutant looters.

Bill Geerhart is the editor and co-founder of the Cold War popular culture website CONELRAD.com. The site launched on July 16, 1999, the 54th anniversary of the Trinity Test.

Don’t miss Motherboard’s documentary on the Atomic Trucker, the Atomic Cafe and more on Cold War culture.

More

From VICE

-

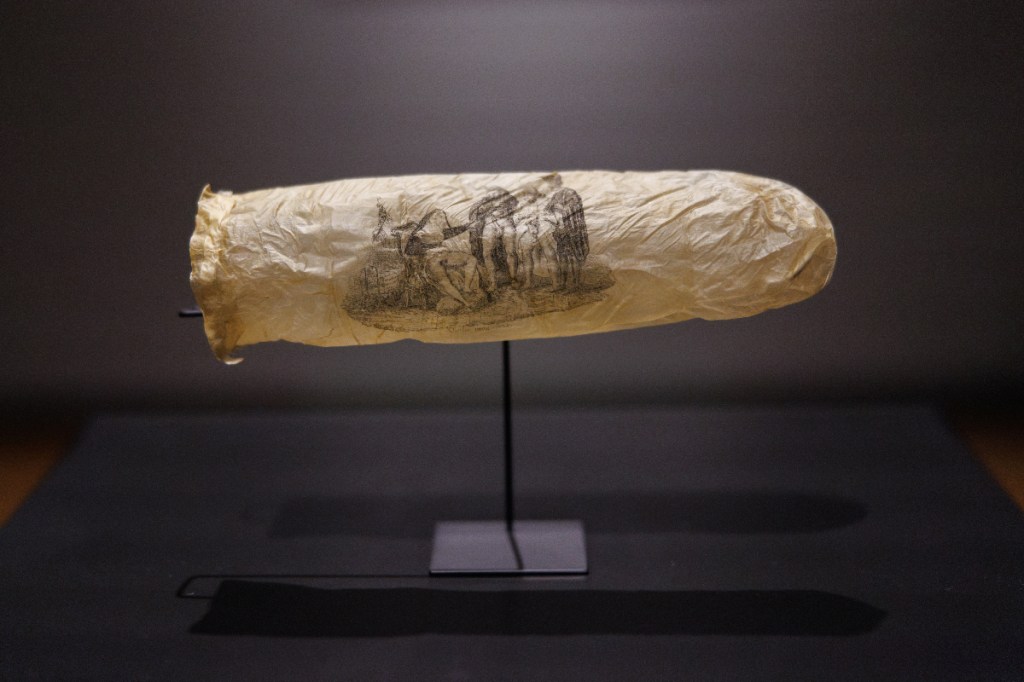

Photo by Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk -

Photo by Tibor Bognar via Getty Images -

De'Longhi Dedica Duo – Credit: De'Longhi -

We Are/Getty Images