TEXT AND PICTURES BY JON FOX

The emblem for the FBI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Directorate features a screaming bald eagle soaring somewhere in the stratosphere, high above the earth where there probably, technically, isn’t much air to soar on. In the background, draped across space, is a huge American flag. The eagle, its talons poised somewhere above, let’s say, Michigan and Montana, is clutching symbols that represent every kind of WMD.

There’s the interlocking ellipses of the atom symbol, the propeller of the radiation warning sign, the universal biohazard symbol, and a bright red beaker that presumably means “chemical weapons.”

In June, the FBI hoisted that banner high over Miami when it threw the first ever Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism Law Enforcement Conference. It had been roughly a year since presidents George W. Bush and Vladimir Putin announced the Global Initiative to Combat Nuclear Terrorism on the sidelines of the G-8 summit in St. Petersburg, Russia. In trumpeting their bilateral partnership, they hoped to spur a greater degree of international cooperation to prevent a nonstate actor (that’s a fancy word for terrorist) from perpetrating a rogue nuclear attack, which everyone pretty much agrees would rank up there as one of the worst things to ever happen.

The Global Initiative began as just Russia and the United States, but since then more than 50 nations have signed on. Just how much multilateral cooperation is really going on is still slightly opaque, though. At the most basic level, they’ve all agreed, in principle, that nuclear terrorism sucks and should be prevented. That’s certainly a good foundation, but what’s the next step in preventing an atomic attack on freedom?

It’s obvious. A government-funded trip to sunny South Florida where the good times never stop. Hence my first sighting of the aforementioned screaming eagle, which was on the cover of the conference program I got when I arrived in Miami to report on the week-long law enforcement event.

It’s obvious. A government-funded trip to sunny South Florida where the good times never stop. Hence my first sighting of the aforementioned screaming eagle, which was on the cover of the conference program I got when I arrived in Miami to report on the week-long law enforcement event.

As business trips go, it was one of the more bizarre ones I’ve been on—and my employer has sent me to Moscow and Staten Island. It was a solid week of talks about improvised nuclear weapons and dirty bombs turning New York City into an abandoned radioactive wasteland. But then there were also the police-escorted party buses to South Beach and a trip to the Orange Bowl where an FBI SWAT team fake killed fake terrorists with real paintball guns. They then defused a fake bomb with something that looked remarkably like Johnny Five from Short Circuit. I watched the whole thing from the stadium stands while drinking government-issue water. Then everyone partied some more.

But let’s begin at the beginning… After getting my press badge early Monday morning, less than an hour after my 6 AM flight from Washington touched down, I stumbled into an enormous, darkened conference room in Miami. There was rousing, epic music playing and about 400 police officers, FBI agents, U.S. government officials, and foreign defense ministry representatives listening to a golden-tongued MC talking about how seriously fucked up nuclear terrorism is. Then he shot it straight over to center stage for a full-blown opera version of the national anthem belted out by a guy in a police uniform. It was sort of like Team America but without puppets.

After a video link to a sister nuclear terrorism conference in Kazakhstan, a speech from the director of the FBI, and some comments from a member of the Russian FSB (which used to be the KGB), a nuclear scientist working with the Homeland Security Department took the stage and said that terrorists would probably be totally happy with a nuclear device going off with the equivalent force of 100 tons of dynamite—less than 1/100th the power of the bomb we blew up over Hiroshima. It would still wreak some incredible destruction, he promised.

But that’s assuming the terrorists could scrape together the fissile material—the uranium or plutonium that remains impossible for a terrorist group to produce on its own. Once they get that, building a bomb is within the realm of possibility.

“It’s not trivial but, as the intelligence community has said, it’s not an insurmountable task,” he said.

Then they opened it up to questions.

There were hundreds of officials, and no one raised their hands. Was this room full of experts and dignitaries really not going to come up with a couple of queries? He asked one last time if there were any questions, and finally I stood up. (Oh by the way, I was the only reporter in the cordoned-off press area. These things aren’t exactly widely covered.)

I asked just how likely the Homeland Security Department thinks it is that a terrorist group would pack a nuclear bomb inside a shipping container and send it stateside. While members of Congress continue to call for 100-percent radiation scanning of shipping containers, some in the domestic-security sector are beginning to suggest that it would be an unlikely way to deliver a nuclear bomb.

“Giving up a nuclear device, putting it in a container and letting it float around the world for a couple of weeks is probably folly,” the head of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office said earlier this year while discussing the threat.

The Homeland Security Department wants to spend more than $1 billion to install next-generation radiation detectors at the nation’s ports, and I was essentially asking if he thought it was worth the expenditure given the perceived threat.

The scientist in Miami dutifully failed to answer my question, and I sat back down.

Apparently I made a mistake in even asking the question. Reporters weren’t supposed to speak. Who’d have known? I mean, that’s what they pay us to do. Yet here it was, mid morning, day one, and I had apparently already angered the FBI organizers and come close to losing my credentials, according to a conversation I later had with a special agent. He looked like some 1950s cartoon drawing of an archetypal American—all blond, straight nosed, and square jawed. Johnny Unitas with Special Ops training, basically. Hadn’t I been “briefed” on the protocol, he asked?

We were both in the elevator, me on my way up to my room on the 34th floor of the hotel.

No, no briefing, I said. All I got was my picture on an orange press badge and an agenda.

“Well, if it was up to me,” he said, “I would have pulled your credentials.” It was hard to tell if he was joking.

Later that afternoon, I wandered around the vendor area outside the conference room. There were people eagerly trying to sell radiation detectors, software that tracks internet usage, and radiation-exposure triage kits. More than one booth was hawking some sort of fancy overhead projector. Exactly what these projectors had to do with terrorism remains unclear to me, but it was at this point it that I began to see one of the true purposes of this conference: selling all kinds of crap to local law-enforcement authorities so that they can feel like they’re going to be ready if terrorists somehow get radiological on their hometowns. It’s pretty much the present-day equivalent of 1950s duck-and-cover drills in grade schools and backyard bomb shelters.

In one stall, a man was trying to drum up interest in a $15,000 remote-control truck capable of pulling a trailer to set a charge near a suspected improvised explosive device. The idea was that the truck could blow up a homemade landmine before it blows up an army Humvee. Again, exactly what this had to do with nuclear terrorism is not entirely clear. As far as I know, insurgents in Iraq haven’t got any plutonium to pack into their IEDs. I’m also not entirely sure why it cost $15,000 considering it looked like pretty run-of-the-mill hobby store fare, except it was painted stealth black and had a swiveling camera stuck on it.

It seems the conventioneers were less than impressed as well. As I was checking my email that afternoon at some computers set up next to the conference room, the remote-control truck crept by my feet. In its miniature pick-up bed was a handwritten sign in ballpoint pen that said, “Follow me to booth 35.”

The truck rolled past me and toward the doors of a conference hall that vendors were prohibited from entering. An FBI guy in a suit began to chastise the truck as if it were a person.

“You can’t go in there. You have to stay in the vendor area,” he said, slightly stooped over, directing his admonishments to the tiny camera on the front of the truck.

A man with a huge remote control panel strapped around his neck turned a nearby corner, apologized, and drove the little truck away.

At another stall, I talked to a young vendor who was selling anti-chemical weapon medical supplies. On the round table in front of him was an array of plastic tubes about the size of magic markers. They were atropine self-injectors minus the atropine and the syringe. They were self-injection training cartridges. Good if you get dosed with simulation nerve gas, I guess.

He let me have one.

“Step 1: Pull off gray safety release.”

“Step 2: Swing and firmly push green tip against outer thigh so it ‘clicks.’ Hold against thigh approximately ten seconds.”

I did this until my technique became exceptional. The next time I’m dosed with nerve gas, I’m going to be on it so fast the terrorists’ heads will spin.

On the conference’s second day, Richard Falkenrath, a former homeland security advisor to President Bush and now head of the New York City Police Department’s counterterrorism division, suggested that the intense focus on scanning the sea-bound shipping containers is misplaced.

“It seems to me that Washington is fixated on one particular delivery system—international shipping containers—for reasons I don’t fully understand,” he said.

He was, in a way, answering the question I couldn’t get answered the day before. He was also arguing that a $40 million initiative to ring New York City with radiation detector equipment shouldn’t be sliced in half as Congress had just proposed.

Rather than worrying so much about shipping containers, people, especially in cities, should be concerned about the vans or trucks that could blend with the crush of traffic and convey a dirty bomb, he said. “That’s the delivery vehicle we’re worried about most.”

In a dense city like New York, such an attack could be “potentially catastrophic,” he said. While it wouldn’t have as great of consequences as an improvised nuclear attack, it is certainly much more likely, he said.

A dirty bomb packed with the radioactive alkali metal Cesium 137 may not kill a large number of people—perhaps no more than a conventional bomb attack—but it could render swaths of the city uninhabitable due to unacceptably high levels of radiation.

A dirty bomb packed with the radioactive alkali metal Cesium 137 may not kill a large number of people—perhaps no more than a conventional bomb attack—but it could render swaths of the city uninhabitable due to unacceptably high levels of radiation.

The isotope could actually bond with concrete and buildings. “You can’t just rinse it off. You have to tear it down and rebuild it,” he said. It would be a “nightmare scenario.”

After a day of talks like this the FBI was happy to shuttle us all over to South Beach to enjoy the bustle of the tourist strip. Perhaps it was done as a courtesy, eliminating the need for a $25 cab, or maybe it was a security measure for the scientists and law-enforcement people enjoying the incredible humidity of a South Florida June, but each night at eight and then again at nine, two buses would leave the hotel for the beach. With a full retinue of Miami motorcycle cops leading the way, we sped through red lights as even more cops blocked intersections and stopped traffic.

Some bystanders smiled at the buses’ tinted windows, more or less everyone stared, and I saw one woman give us the slowly rotating wrist and cupped palm of the British royal wave.

Then at 11 and again at midnight the buses and motorcycle escorts would return to hump us all back to the hotel. That first night, as I climbed onto the 11 o’clock bus, a woman from some Eastern European nation’s defense department posed in front of one of the jack-booted police officers as a colleague took a photo.

On the ride back I sat next to a terrorism consultant from Romania and made small talk.

The next day, I approached one of the vendor booths where two guys sat reading the newspaper next to a mannequin in a black radiation suit. For about $1,000 the whole get-up could be yours and you’d be pretty much OK in the event of a dirty bomb going off down the block, they said. They offered to let me try on what felt like a very heavy wetsuit.

So this is good against a dirty bomb, but let’s say a nuclear bomb goes off on the other side of the city and you didn’t happen to die in the initial blast. Will this do anything to protect me from that radiation? I asked.

“You’re pretty much screwed then,” the bigger of the two guys said. Boots, gloves, and respirator are sold separately. I was assured I could get them relatively cheap.

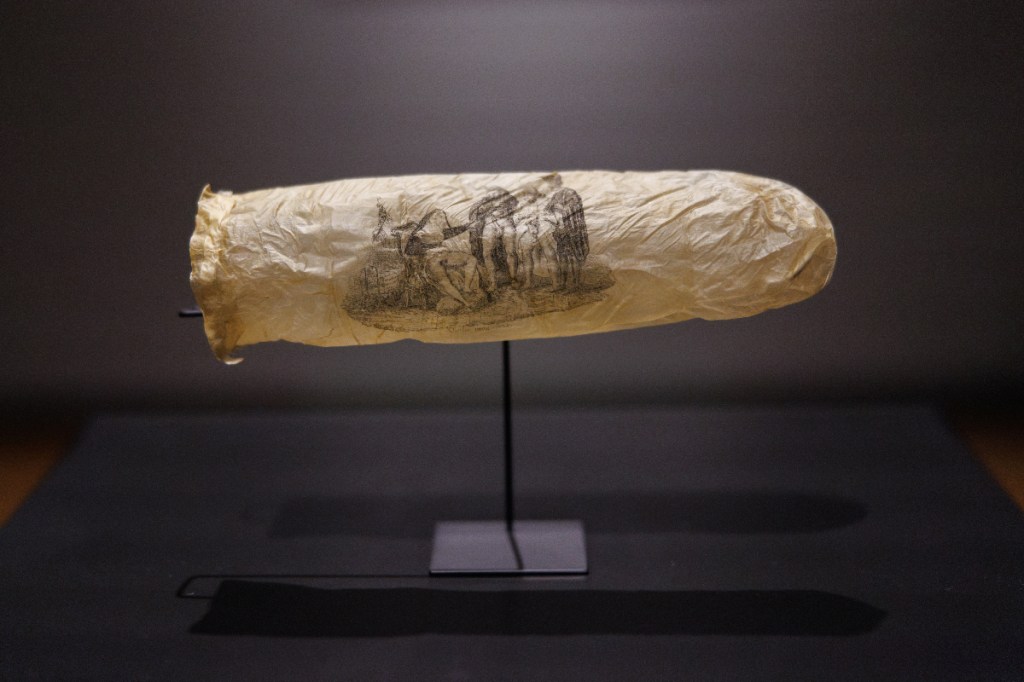

On Wednesday, everyone was bused over to the Orange Bowl (again with the motorcade) to watch what turned out to be an underwhelming demonstration of a simulated response to a simulated dirty bomb in a simulated warehouse. An assault team repelled from a Blackhawk helicopter behind a nearby grove of palm trees. Apparently they had planned to have the SWAT team drop right into the stadium, but the rotor wash from the copter would have knocked down all the mesh partitions that were standing in for warehouse walls. Once the would-be terrorist bombers were neutralized with paintball assault rifles, the bomb squad brought in a rickety-looking robot [pictured above] to shoot a small metal box with some water that had been packed inside shotgun shells.

And voila, in a burst of agua the box was pushed off a table and the firing circuits in the device were dislodged! Simulated crisis averted! The crowd erupted in riotous cheers. (Just kidding. Nobody said anything.)

On my last night in Miami, I took the party bus back into South Beach. By 10 PM I was in Mango’s Tropical Café. Waitresses in skin-tight, animal-print pantsuits were taking turns getting up and halfheartedly dancing on a horseshoe-shaped bar in the middle of the club. The place was filled with FBI agents in shorts, untucked shirts, and unwaveringly sober haircuts. There were U.S. government officials and foreign representatives. There was the guy who had given a lengthy and mind-numbing PowerPoint presentation earlier in the day. He was eating dinner at a table a few feet away from a woman shimmying on top of the makeshift stage. One of the FBI’s joint terrorism task forces from a northeastern city was milling around near the entrance. Even closer to the stage was a table full of Bulgarians—three men joylessly chain smoking and one woman. They weren’t talking and didn’t seem to be watching the show until a bouncer lifted the female dancer down off the bar and three men got up on stage and began a coordinated dance routine that ended with bare male chests. The Bulgarians turned to look and were apparently displeased. They left shortly thereafter.

The dancing waitresses in their remarkable pantsuits resumed their turns on the bar stage, and I spent my last night in Miami drinking beer with a guy who had “top secret” security clearance, shoulder-to-shoulder with G-men. I can only hope the FBI is already working on next year’s conference, in Las Vegas perhaps. The brighter our lights shine the more the terorists hate us. Dance, girls, dance!

JON FOX

More

From VICE

-

Photo by Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk -

Photo by Tibor Bognar via Getty Images -

De'Longhi Dedica Duo – Credit: De'Longhi -

We Are/Getty Images