James Blake’s “CMYK” might’ve been the most talked about song of 2010. This was not necessarily because of the music. Sure, the warped, beatific vibes propelled the then-21-year-old songwriter out of dubstep forums and into international consideration, but the critical traction and thinkpiece-fodder came from a much more inconsequential place, namely the semi-obscured samples of Kelis’ chirp and Aaliyah’s coo. Two fragments of displaced ‘90s R&B amber, swirling around in the middle of an ordained Very Important Song. It certainly didn’t match our calculations.

Blake would spend a lot of time answering interview questions about Aaliyah, usually punctuated with the predictable sentiment of “I don’t know, that’s just what I grew up listening to.” Everyone was so desperate to find a storyline, even when it was abundantly clear that James just did what came naturally. He was not the only one; guys like Shlohmo, The Weeknd, and How To Dress Well all did their own narcotic tributes to the same fuzzy-warm pop—in 2012 the notion doesn’t even raise eyebrows. ‘90s R&B certainly wasn’t a critically cherished scene; in fact, it was pretty much left to die with the 20th century. But in what has become a recurring theme, the people making the music weren’t concerned with any unhip dogma. Instead, they synced up their influences, completely phlegmatic and unaware to what’s currently chic. Listeners like you and me have always operated with a blacklist, but James Blake and plenty of other worthy artists have proven that everything, no matter how marginalized, is relevant.

Videos by VICE

It’s not bravery; we’ve seen a substantial pattern of people making serious music with disposed, frivolous ingredients. Wavves basically made a Blink 182 album in King of the Beach, and Vampire Weekend have thrived on No Doubt’s bounce for two whole records. Bon Iver talked a lot of game about Bruce Hornsby and closed his de facto 2011 Album of the Year with what was essentially a Lionel Richie tribute. I don’t think any of these people considered their so-called trailblazing with furrowed I’ll-show-them vigor; honestly, they don’t seem to give it any forethought at all. Why should they? It’s practically in their D.N.A. Revivalism is not a product of choice as much as it’s a product of roots. How are we supposed to be surprised when Nathan Williams, the kid from the sunburnt, disheveled side of San Diego, sneers like Tom DeLonge? Or that Justin Vernon, a near-Aryan-looking dude from the rural Midwest, wants to cover Bonnie Raitt? There’s no agenda or iconoclasm here, that’s just the way influence works, they make the records they want to hear. It runs completely independently of what the actual listener thinks is “dope.”

The music press has a weird way of revising history out of the respect of the people we’re covering. It’s almost as if we wait until something out-of-date and peripheral manifests itself into something modern and awesome. There’s been a massive influx of reflective music blog essays on the resonant greatness of entities TLC or Green Day, which is stuff that’s been undisputed by the mainstream crowd for years. We all grew up on pop music, which is not always a fact the Pitchfork generation like to admit openly. But music, by and large, does not operate in the confines of taste, which occasionally breaks down walls. Bands never measure anything in terms of guilty pleasures, and that can have a very liberating effect. That Animal Collective, essentially (albeit unfairly) the poster-child of obtuse, restrictive indie, can awaken ancient, long-neglected feelings for the Grateful Dead should be taken as a deeply reassuring thing. Music culture has always been about image, but the actual music behind it remains as truthful as ever.

I should mention that the one exception to this rule is, of course, nu-metal. Despite its once-ridiculous popularity and total cultural penetration, nobody, not even the kids who grew up with it, has managed to find any joy in any of its aesthetics. I guess it’s pretty amazing to think there was one movement so noxiously maligned it’s practically impossible to revive. You could point to Death Grips, but that’s a stretch at best. At this point, it seems that nu-metal will never be cool again, which is both hilarious and tragic.

But I digress, the main thing we can take away from this trend is that there are some things about the music industry we don’t have to be cynical about. At the end of the day, everything runs through the music, artists decide what’s fashionable, worth attention, and deserving of tribute. Sure, we might edit it down, but we’re always reacting to what a musician has to say. It’s a lot of power, but it’s hardly ever used maliciously, or even consciously. It’s really hard to question the genuineness of what a musician likes, and that purity remains remarkably underrated. In a listening culture caught up in image and self-consciousness, the honesty of the music transcends every division we may have set up for ourselves.

More

From VICE

-

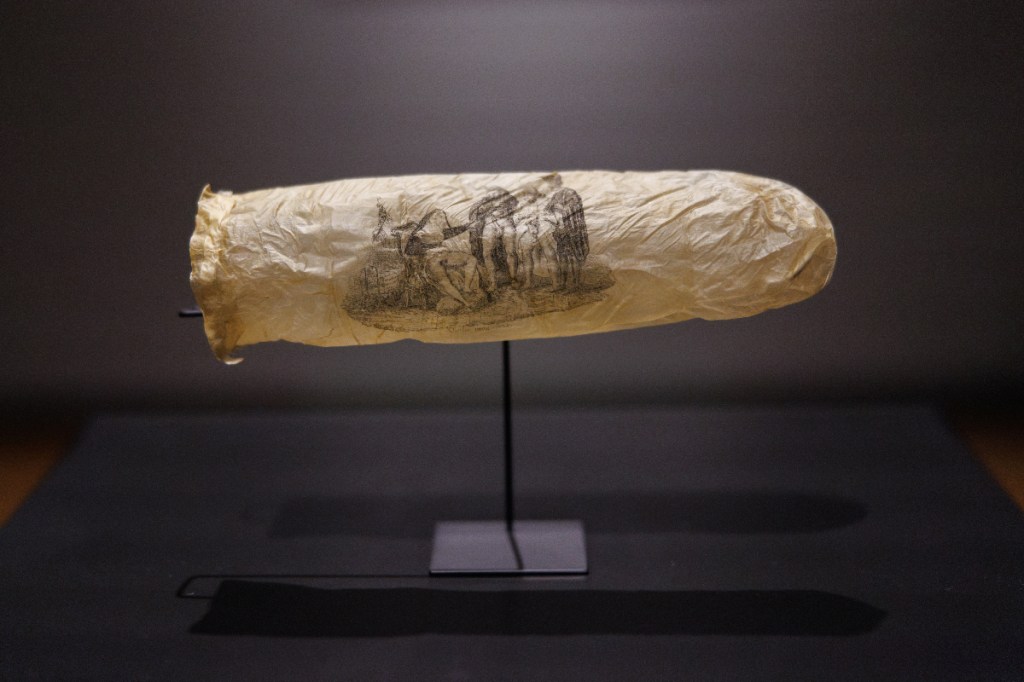

Photo by Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk -

Photo by Tibor Bognar via Getty Images -

De'Longhi Dedica Duo – Credit: De'Longhi -

We Are/Getty Images