Photo: Daniel Orth/Flickr

Add another bad thing that’s brought about by air pollution: Increased risk of insulin resistance, the precursor to diabetes, in children. Research published in the journal of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes shows that for every 500 meters closer to a major road a child lives, insulin resistance increased 7 percent.

To determine this the scientists examined blood samples from 10-year-old German children, determined the estimated exposure to traffic-related air pollution in each, and accounted for other factors which could skew the results such as socioeconomic status, their birth weight, BMI, and exposure to second-hand smoke in the home. In all cases the models they used showed that levels of insulin resistance were higher in children with greater exposure to pollution.

Videos by VICE

Talking about the implications of this, report co-author Joachim Heinrich says,

Moving from a polluted neighborhood to a clean area and vice versa would allow us to explore the persistence of the effect related to perinatal exposure and to evaluate the impact of exposure to increased air pollution concentration later in life. Whether the air pollution-related increased risk for insulin resistance in school-age has any clinical significance is an open question so far. However, the results of this study support the notion that the development of diabetes in adults might have its origin in early life, including environmental exposures.

The report concludes, “given the ubiquitous nature of air pollution and the high incidence of insulin resistance in the general population, the associations examined here may have potentially important public health effects.”

Stats from the American Diabetes Association show that 8.3 percent of the US population, both children and adults, have diabetes. That amounts to 25.8 million people, including 7 million people who don’t know they have it. Over triple that number of people have pre-diabetes. The rate among non-Hispanic blacks and Hispanics is roughly one and a half times that of non-Hispanic whites and Asian Americans. All of those states are age-adjusted, but rates get higher as people get older—for US adults over 65, the diabetes rate is a hair under 27 percent.

Image: CDC

Looking at the rate of increase in diabetes cases diagnosed annually, the Center for Disease Control’s Diabetes Report Card shows a dramatic increase in the past three decades, as the image above illustrates.

At current rates of increase, a 2010 CDC study projected that by 2050 one-third of US adults could be diabetic.

Consider how this research could fit into the bigger picture of increasing urbanization (and therefore increased exposure to traffic-related air pollution), combined with rising obesity rates (not helped by sedentary lifestyles and car-centric culture), and lack of access to quality food in poor urban areas (food deserts). There needs to be more research to see how connected those factors are, but they appear to all be feeding into the same health problems, and the air pollution connection just adds another piece to the puzzle.

For example, 80 percent of people in the US live in urban areas today, which has risen from two-thirds in the 60s. Though the obesity rate in the US stabilized last year, 69 percent of adults are overweight or obese, with 36 percent being obese; for children and teens, 32 percent are overweight or obese, with 17 percent in the latter category. In the 1960s, just 11 percent of the population was obese.

Food deserts and lack of access to quality food is harder to quantify in simple statistics, but the rise in predominance of processed food and fast food, as well as food portions of junk food, should be obvious if you’ve been even halfway paying attention to the issue. In New York City, studies have shown that a lack of access to healthy foods has been directly correlated with health risks like obesity.

Like all health problems, individual responsibility is paramount, but in many ways in this case there are systematic factors in the way we have constructed our towns, lives, infrastructure, and food systems that are working against creating a healthy population—particularly if you live in poor, urban areas.

More

From VICE

-

Wildpixel/Getty Images -

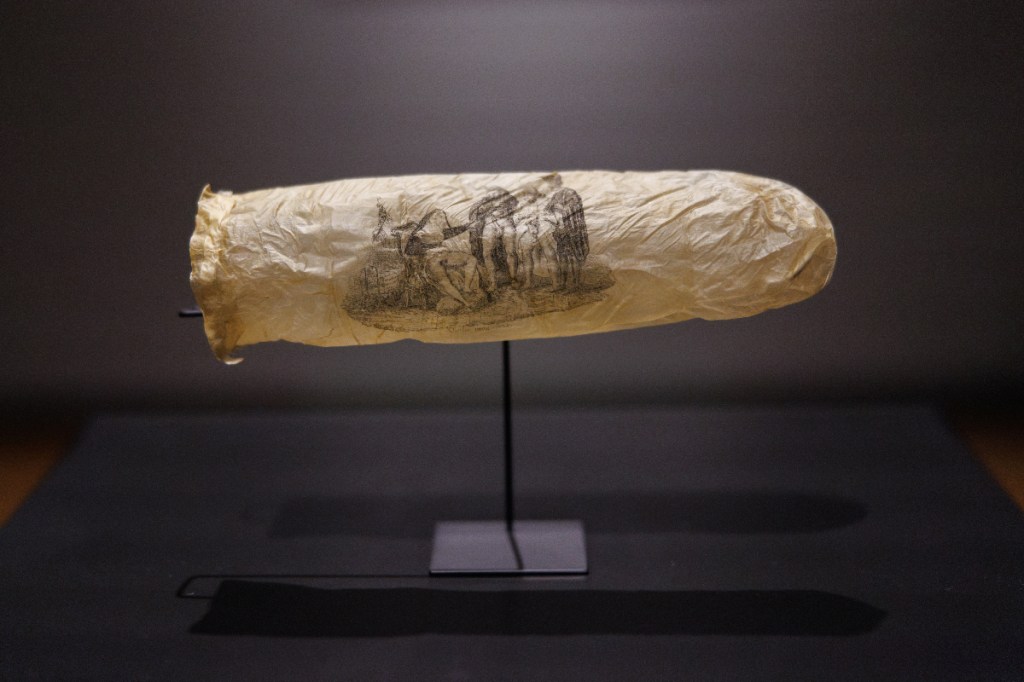

Photo by Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk -

Photo by Tibor Bognar via Getty Images -

De'Longhi Dedica Duo – Credit: De'Longhi