What does having Indonesian heritage mean to you? That’s a loaded question that Teta Alim, a 24-year-old writer based in Washington DC, asked other Indonesians she’s met abroad for her zine Buah.

Teta, who was born in Indonesia but has spent much of her life in the US, continues to wrestle with the question herself. As she’s finding new answers about her identity, she invites others to do the same. Buah, at its core, is about the internal and external struggles experienced by Indonesian diaspora worldwide. Her zine includes interviews of people from different disciplines and walks of life, who often challenge the mainstream perception of what it means to be Indonesian in an age of nationalist identity politics. What they all have in common, however, is a shared sense of connection to their heritage.

Videos by VICE

In an interview with VICE, Teta shares her story of how her own journey as an Indonesian living in the US fostered the creation of Buah and the intersections of identity it explores.

VICE: Let’s start it off simple. So where were you born and where do you call home?

Teta Alim: Those aren’t simple questions! [Laughs] Well, I was born in Jakarta, Indonesia, but I came to the US when I was 6 months old. My family moved to Ithaca, New York, and that’s where I lived until I was 18. In terms of what I call home, it’s hard, because I want to call Jakarta my home—that’s where all of my relatives live except for my parents and my older brother—but I was raised in Ithaca.

What was it like growing up as an Indonesian in Ithaca?

Cornell, the university my father was attending when we moved, has a very strong program for Indonesian Studies. [The historian] Benedict Anderson is from there if you know about the Cornell Paper that came out in the ‘60s. So in terms of knowing Indonesia as an entity it’s not weird to be in Ithaca, and there was a community of Indonesian students there, but everybody tended to go back home after a while. In the end my family was the only one that stayed in the area, so even though I grew up with an Indonesian community in elementary school, that kind of disappeared by the time I was in middle and high school.

Watch: These Are The People Traveling To The U.S. On The Migrant Caravan

What have you learned about identity from interviews you’ve done with people of Indonesian heritage overseas?

It’s interesting because it depends on how people were raised and how their family treated it. A really big factor is how they came to the country they settled in. It’s really different if you came in as a refugee from ‘98 or if you moved because your parent was a student. It also really depends on your relationship with your family. People who may not have a good relationship with their parents or their family may not be interested in that aspect of themselves, and that’s fine as well.

A lot of times I’ve noticed that people are finding out about [our history] on their own, or that they’ve had to squeeze it out of their parents. With the older generation it might still not be something that they’re comfortable talking about. Fortunately, in my family it was something we were pretty open about and we never shied away from discussions about history and past issues.

So where does Buah fall into the mix?

Buah Zine is a space for people to grapple with their heritage wherever they are at. I feel like I’m always learning about my heritage and I’m limited to what I know. My background is Javanese, Gayonese, and Sundanese, so I know about Java and Sumatra but I don’t know much about Kalimantan or Sulawesi. I feel like there’s never an end to what you can discuss about Indonesian heritage, especially regarding our history. There are so many complicated things that we haven’t even begun to talk about in terms of colonialism, and we need to confront so many things about the past before we can really see where we’re going into the future.

In Indonesia, nationalism and the push for a singular national identity are on the rise. What do you think of that?

So the reason why I chose the term “Indonesian heritage” instead of “Indonesian” is because I’m trying to divorce the term from borders and passport identity. We absorbed these borders from the colonial era and they don’t actually make sense in today’s world.

I obviously have a lot of pride in my heritage because it’s where I come from and where I derive a lot of my values from. But at the same time I’m just not interested in nationalist rhetoric—for example, the term “pribumi.” It’s such a fraught term that you can trace back to racial hierarchies in the colonial era.

It’s interesting because Indonesia touts its diversity a lot of the time but it doesn’t walk the walk. In reality you can’t be a person in a minority religion or even a person in a minority ethnic group. I hope to show with Buah that diversity is not just a veneer, but a reality in a country so friggin’ diverse that it’s hard to say what “Indonesian culture” is outside of the Javanized canon.

How have the people you interviewed dealt with the disconnect between heritage and national identity?

This is kind of a cop-out answer, but I feel like everyone deals with it differently depending on at what point they are in being abroad. If you go abroad during your college years you’re more prepared to find people of Indonesian heritage or other like minded people, but it’s hard, because even if you’re Indonesian, sometimes that’s the only thing that you have in common.

I studied in London my senior year of college, and that was the first time I went to an Indonesian group at a university. I met some really cool people, but I quickly realized that aside from being Indonesian we had nothing in common. Most were international students who didn’t grow up in London and were going out to Denmark or swanky restaurants on the weekend, and that just wasn’t me.

I guess that’s the hard part of being Indonesian for me, because not only are there so many ethnic and religious differences, there are also huge class differences I have to contend with that are absent in the States.

When I was younger I noticed that diasporic communities are actually pretty fragmented. For example, the people who frequent the local mosque in DC would hang out, embassy people and diplomats would hang out, and the Christian Indonesians would hang out, all in different groups. Sometimes there’s overlap for people who grew up here, but often there isn’t, and that makes your overseas Indonesian community feel smaller than it actually is. In the whole US there are so few Indonesians, I think like 113,000 in the last census, that I wonder what’s the point of all of this division. It would be nice to have a space where we could just come together.

How has your personal journey influenced the creation of Buah and the intersection of identity it explores?

It’s definitely influenced it a lot. I actually try not to be so US centric—I have interviews from people who have lived in the UK, Hong Kong, and Australia, which are all very different perspectives on growing up abroad. Before I made Buah, I saw the that there wasn’t a space to inspect Indonesian heritage removed from Indonesia and I was waiting for someone to create it. When I saw that there still wasn’t something, I was like, OK, I’ll do it.

You feature a lot of queer Indonesians in the zine. Is that intentional?

Like I said, my heritage is Javanese and Sumatran, and I grew up Muslim, so it is really important for me to give a space for people with different religions or people who don’t have a religion to be speaking at Buah. I also think that providing a space for people who identify as LGBT is especially important to highlight the fact that you can be Indonesian and also be gay, like it’s not such a revolutionary idea no matter what the government says. If you’re both Indonesian and gay I want you to know that you’re not the only one. Just know that you have a community out there and that you don’t have to feel alone.

I’ve been asked by guys if they can speak on my magazine because I have a lot of women and non-binary people speaking. I’m not limiting it, but it just so happens that the people I’m connected to are mostly women and non-binary folks. If more men are interested in speaking that would be great, and I would love to get that perspective because I’ve been thinking about what masculinity means from an Indonesian point of view.

Where do you see Buah going in the next few years? Do you have any schemes in the works?

Honestly, I hope to be able to travel to areas where there are large diasporic communities. I would love to learn more about people of Indonesian heritage who were taken to Dutch Suriname, South Africa, and the Netherlands because that’s such a fraught part of our history that’s rarely discussed. I want to start learning more about these different communities and compiling things in a way that is accessible.

What I’ve found through these interviews is that Indonesian heritage is very connected to an ability to speak Indonesian, but there are also a lot of people of Indonesian heritage who don’t know how to speak the language. I do want Buah to be a bilingual site at one point. I want to be able to translate the English interviews into Indonesian and vice versa so that more people can access it.

Read some interviews by Buah below:

Physical copies of Buah Zine will be sold at Bandung Zine Fest on 24 November. The online version of the zine is available here .

Get in touch with Teta on Instagram or her website .

More

From VICE

-

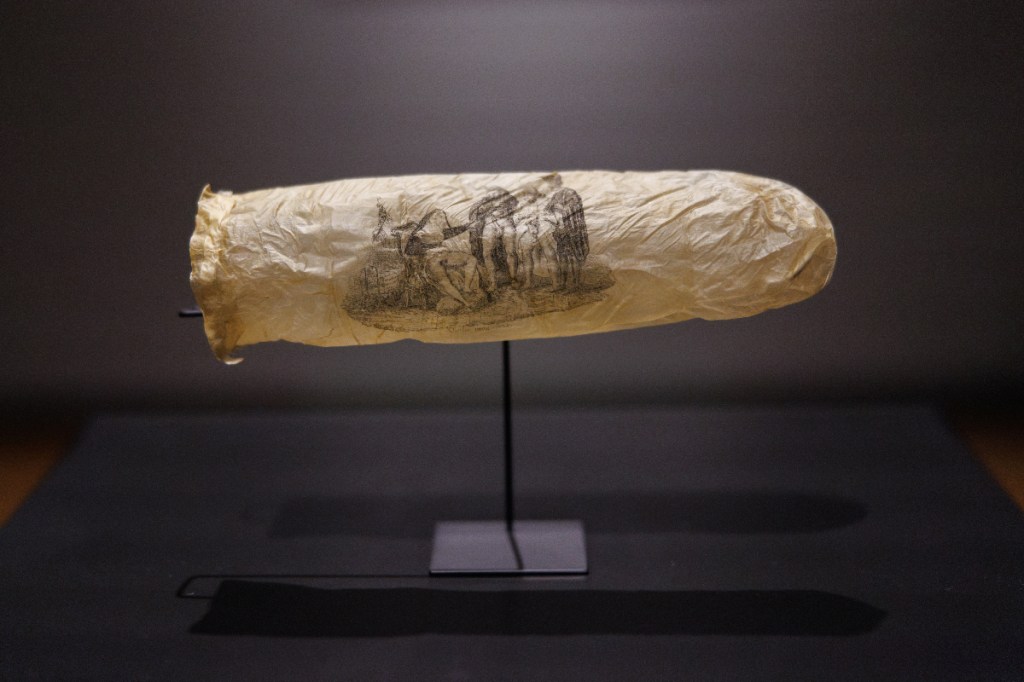

Photo by Rijksmuseum/Kelly Schenk -

Photo by Tibor Bognar via Getty Images -

De'Longhi Dedica Duo – Credit: De'Longhi -

We Are/Getty Images